Tiempo y Pensamiento (Time and Thought), Damià Díaz’s (Alicante 1966) multi-disciplinary installation represents, in the style of Kavafis, his unusual journey to Ithaca. When he set out on the road, whose ending he has yet to reach, he encountered adventures and knowledge. With the desire to go ever further, he went on to gain knowledge from the learned ones and came across previously hidden doors. Always with the idea of Ithaca in his heart and in his mind and that arriving there was his destiny. Enriched by everything he accomplished on the road, not expecting anything more than a wonderful voyage.

With this exhibition, the author embarks upon a new creative stage, using different media, techniques and dimensions, where the painting departs from its usual format to give way to volume.

I know, having seen him dock at certain ports, that it has notbeen an easy road to follow. His academic and professional training have prepared him in three main disciplines: painting, engraving and stage design. His perfectionism has led him to carry them to extremes in order to extract the maximum expressiveness from each of them. Tiempo y Pensamiento (Time and Thought) has been an excellent artist’s exercise, as can be seen in the final result.

The installation consists basically of paintings. Damià Díaz belongs to a group of artists who haven’t abandoned painting, despite those who predicted its inevitable demise, because he believes in it deeply and has discovered the conceptual possibilities of the subject. He has faced up to the desolation of shape with a taut canvas and with other materials such as steel, methacrylate and wood, all with colour as the common denominator.

He uses a Mediterranean palette, continuing the saga begun by his grandfather, Damián Díaz (1910-1984), and carried on by his father, Pepe Azorín (1939), and sister, Lorena Díaz (1968). Four very different ways of understanding art and painting, but all of them part of a deep-rooted family tradition of an enormous love for art and an excellent command of technique that they all learnt as children.

This exhibition is a result of the process described above and has grown and developed as a process in movement – since our conversations in spring 2000. As one of the organisers, I saw the genesis of the project and the difficult path that has been taken. As a point of interest, the artist studied and immersed himself in the work of Eadweard Muybridge (1830-1904), a pioneer of photography and the first person to break down the moving image into its constituent parts. This aided him in his search for ways to resolve the maze that is to be found as soon as you enter the installation and of which he has made hundreds of paper sketches and filled many of the travel notebooks that we both like so much.

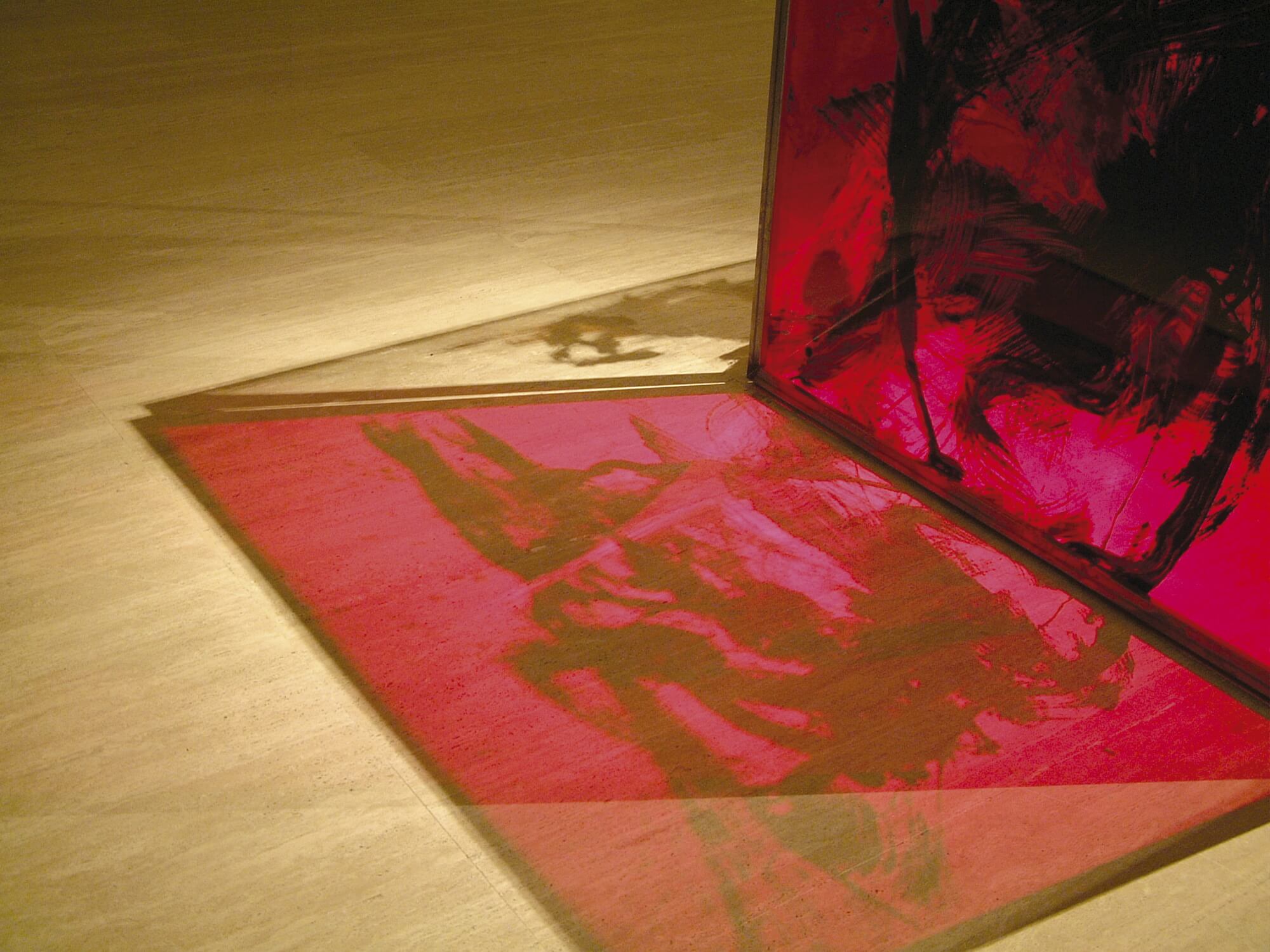

The pieces presented are basically conceived as a large pictorial installation where the spectator is an important part of the pieces themselves, reformulating the relationship between creation and perception, the fusion of painting on a translucent support, the light falling on it and its own projection. A space where one can lose and find oneself between reality and its reflection. There are even, as the visitor will find out, two moments within the installation, one that is daytime, reminiscent of the great gothic stained-glass windows and another that is night where the reflection of the piece itself interacts with the passer-by’s shadow. Although a piece in its own right, it creates a split in the light that is projected through the piece onto the floors and walls. Its reflection produces “another piece” that is blurred or deformed and that interacts with the actual object and the spectator.

Damià Díaz’s most important challenge, in his own words, was to establish a balanced dialogue between the space of the enormous room and the pieces. These large formats had already been successful in the Chapelle Saint-Louis in the l’Hôpital de la Pitié-Salpêtrière in París, where some of these works were exhibited in January 2002. However, in Room 365 of the MUA, the artist has added another two sequences, through which he has conjugated the changing effects of the natural light and the architecture of the room to create an atmosphere enveloping light, painting and reflections that involve the spectator, creating a pictorial maze in which the human body is the leading player. A tensed body is the protagonist of a confined space that symbolises society itself and the limitations it generates.

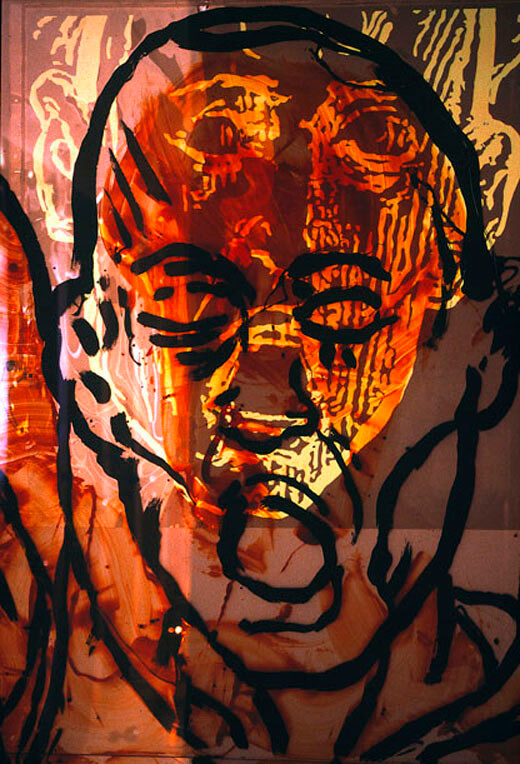

For Damià Díaz, painting is above all a vehicle for expression through which he makes his emotions and moods known. In this sense, his painting could be defined as expressionist. The material methacrylate, which is used as the medium, enhances the emotional charge of the pieces, through which several dichotomies appear: the fragility of the translucent support contrasts with the strength of the metal frames; warm colours are used alongside blacks; and ample, aggressive brush-strokes stand out against the more liquid and fragile nature of the resins.

This Damià Díaz exhibition suggests a constant transit or journey through physical time and time that lives on in memory, in thought. Time necessary to think about oneself and about a world of vague memories that materialise in the shadows of the paintings cast across the floor.

The artist thus concludes the messages embedded in his previous work: the idea of movement, of time, of the passing of life and of the body as an icon, the object and subject that symbolises all areas of knowledge.

The first part of the exhibition, the first sequence – Time -, is in turn divided into three series: Tránsito (Transit), Reflexión (Reflection) and Autoretrato de una secuencia (Self portrait of a sequence). In the first series, Transit, the journey is made through a maze that consists of thirty large transparent sheets in four colours (glass, yellow, red and blue). Painted images are depicted on these sheets and lights are projected in different directions, tracing the imaginary journey of the individual and creating a composition that is projected into the space and onto the spectator, causing them to interact. Damià Díaz has attempted to create the maze at a point where the human being loses and finds himself, becoming yet another part of the composition. The middle series, Reflection, located at the very centre of the room, consists of three large cubic prisms that depict unsettling faces and self-portraits on their four sides. Here, allusions are made to the different states of mind that guide us to a thought. The artist offers possible alternative compositions of vision and reflection, uniting a past and present of experience, events and private journeys. In addition, the light is projected here in one direction only and symbolises the combination of factors that lead us to conceive an idea.

This first part ends with Self portrait of a sequence, where Damià Díaz, using a glass showcase to lend three dimensions to the work, conveys the journey of a character who is moving forward – alla maniera of Muybridge – struggling, tiring, climbing, climbing down, or walking back along a road that symbolises life. At the same time, this character casts a shadow that is a dim reflection of himself. Physical time and time that lives on in memory reappear. A “lay altarpiece” with absolutely no religious connotations, made with man in mind before anything else, before any god.

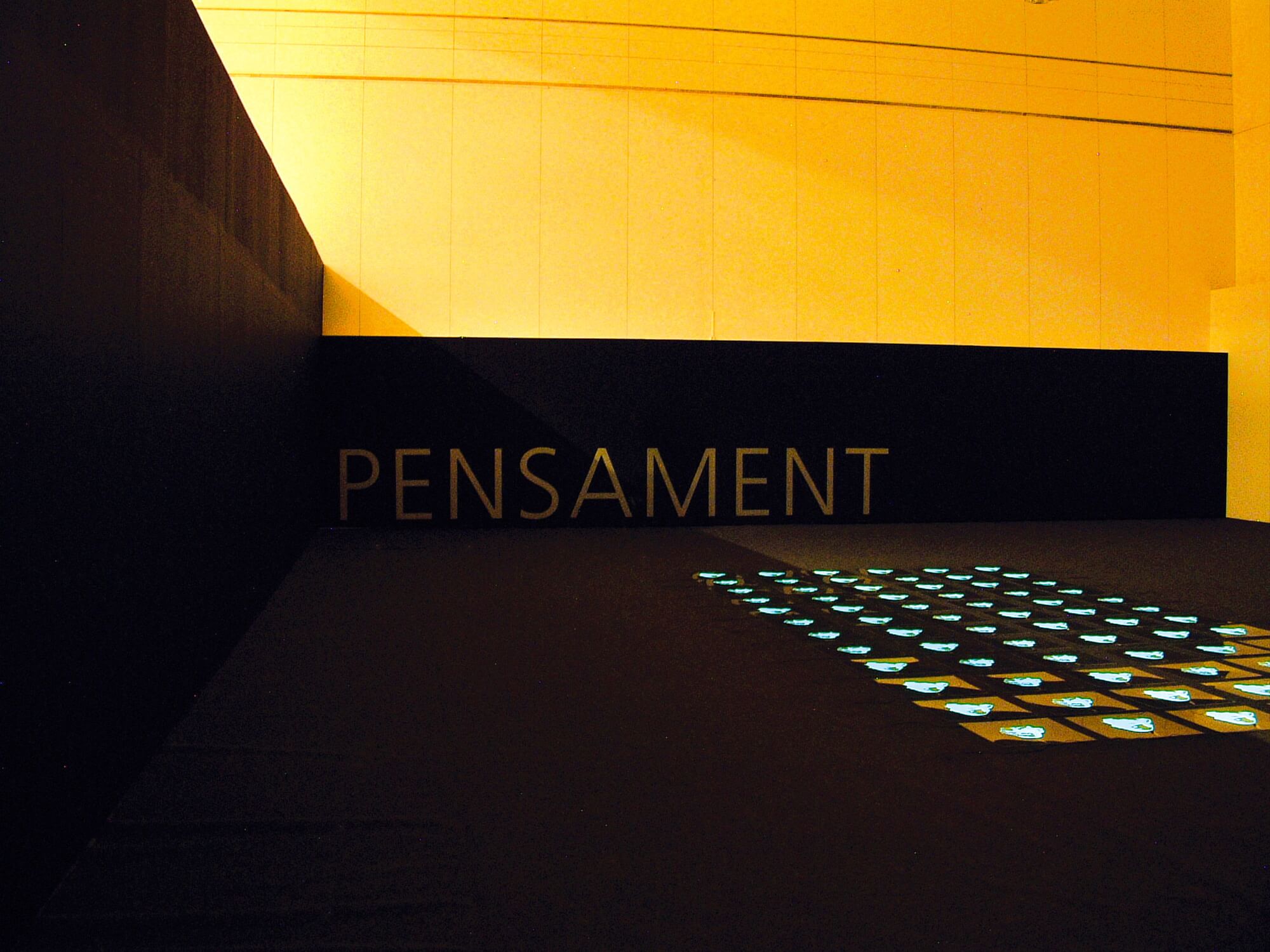

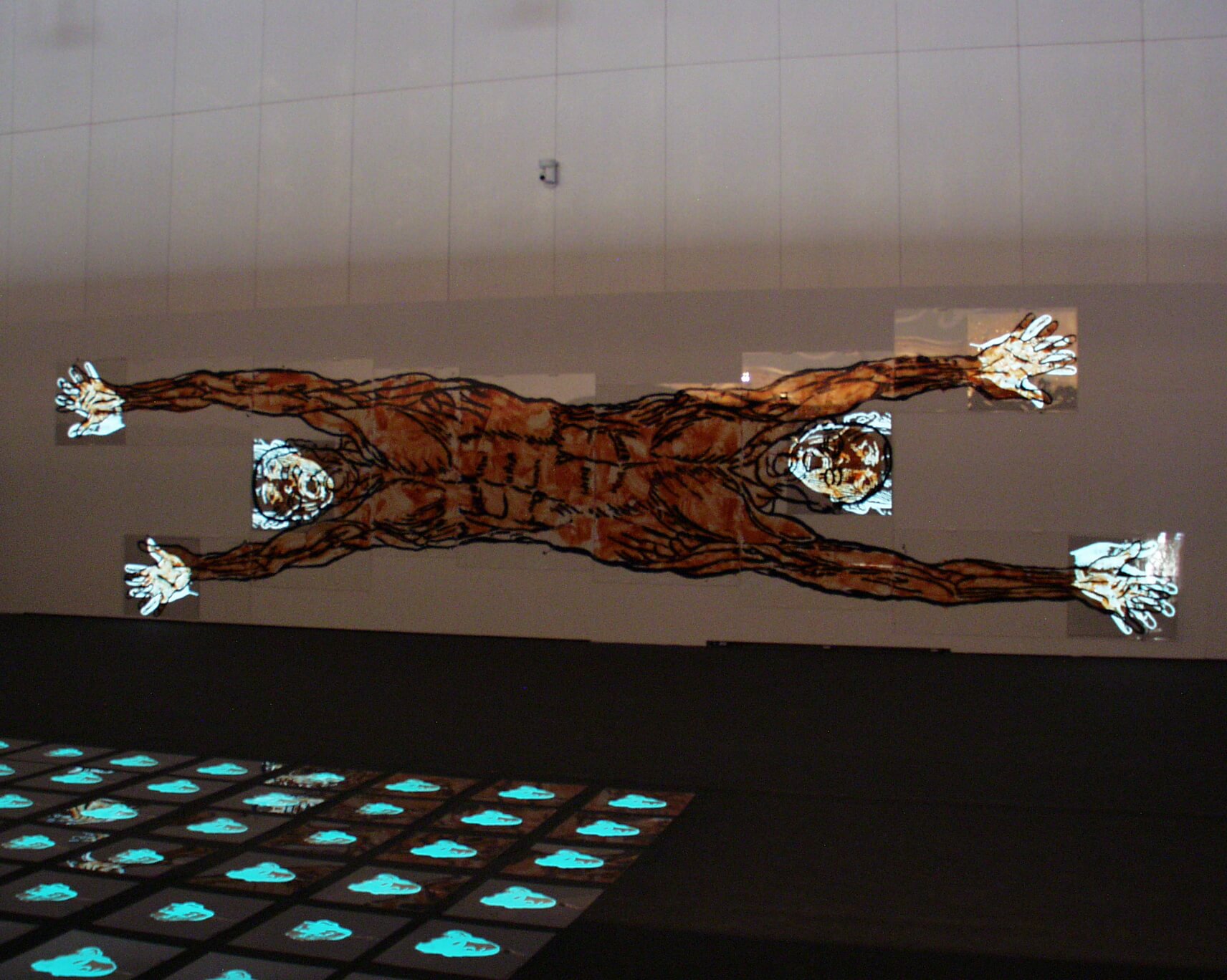

The last part of the exhibition – Pensamiento (Thought) – consists of two pieces that reflect on the world of thought. Journey is a road from the past towards the future. On a black floor and in the darkness of the room, there are seventy luminescent plates, painted on a translucent medium with zinc phosphate and silver. Sixty faces are shown – old sketches that resemble engravings, a constantly changing construction with an ephemeral life of a thousand hours. Consequently the piece adopts a precarious nature, as if it were a performance, that will disappear at the end of the exhibition, giving way to an open road that visually leads the spectator to the last composition. To round off this exhibition, the spectator finds himself in front of a large mural depicting with the image of a man coming out of himself, a new man leaving an old one. This idea follows on from his previous works, a true “miocentesis” of man himself – as if he were a cell – a symbol of renovation, resurgence, the myth of the infinite return.

Since his first exhibitions, Damià Díaz has always presented himself in this way, laid bare for the spectator to see. It has always been his body and soul in every fragment, in every brushstroke.

Using the words of Eduardo Chillida, “I don’t know the road, only its smell”, Damià Díaz defends his ability to enjoy the creative search, considering parallel introspection and outward expression to be of vital importance. The substance of a work of art depends on an experience that the artist has had. Or rather, it is an experience and should not be a hieroglyphic that needs to be deciphered. There is nothing to decipher in it. Let’s leave time and thought behind to understand it together.